| Contents | Start | Previous | Next |

He freaked out; he was not used to being held accountable or having his authority questioned. He needed a way out, so he offered us a six-week temporary permit. Even though it made him late to opening night at the opera, he held a press conference to announce this "settlement" and called Food Not Bombs "pioneers in the effort to end homelessness and hunger."

* * *

In the summer of 1989, the homeless in several cities across the nation created communities for support that they called "tent cities." Tent cities became major actions for Food Not Bombs in New York and San Francisco. These tent cities brought the humanity of the poor to the public eye. Mayors in both cities were in crisis because of the homeless situation, which was getting worse, and because of violent attacks against the homeless by frustrated taxpayers. They had no solutions to poverty because they were unwilling to address the fundamental failures of centralized authority. This resulted in the mayors' highlighting their own inadequate "solutions" to this dire situation. At the food tables in San Francisco, the homeless told stories about how, the night before, police came into the park, beat people, and destroyed their camps. Some were hauled off to jail. One night, the fire department came and sprayed them with water. On another night, the police drove into the park, shone floodlights on everyone, and threatened them over a loudspeaker. After three days of this, people asked us to help stop the police attacks. We moved our daily noontime food service from United Nations Plaza to City Hall. We started serving at 5 o'clock P.M. on June 28 and served hot meals 24 hours a day.

The homeless had created a tent city across the street from City Hall in Civic Center Plaza. Tent City created hope and encouraged self-empowerment. The mayor would threaten to send in the police, but the community would rally together. After the mayor ordered that the "residents" of the park could not use tents or sleep there at any time, there was a spontaneous march to his office, where a giant Food Not Bombs banner was hung from his balcony. On July 12, the Police Activities League moved a carnival complete with bumper cars and Ferris wheels into Civic Center Plaza; the fair was named after "Emperor Norton," San Francisco's most famous homeless person of the 1 800s When we saw the police, we feared we might be arrested to make room for the carnival, so we placed several of our buckets of soup out of sight. On Thursday, July 13, at 6 o'clock P.M., the police moved in, arrested several people, and took the soup we were serving. As soon as the police left, we were back with more soup and bread, and when they walked by again, they found us serving and arrested us again. The fact that we were able to bounce right back several times was a real embarrassment, the kind they would feel many more times in the coming years.

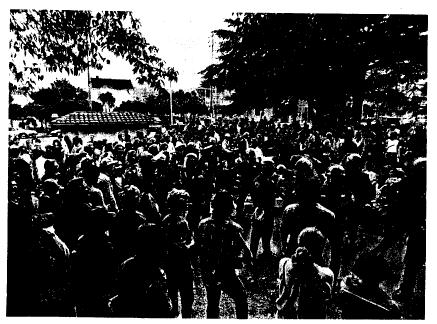

At noon the next day, in response to the arrests, a large rally developed at City Hall. Food Not Bombs brought more food for lunch, and one group of people, inspired by the Tiannamen Square protests that May, came with a 15-foot tall "Goddess of Free Food" complete with a shopping cart in one hand and a carrot in the other. Again, riot police were in the wings. When the giant Food Not Bombs banner was unfurled on the steps of City Hall, the people holding it were arrested.

54 volunteers are arrested serving free food at Golden Gate Park, Labor Day, 1988. Photograph by Greg Gaar.

| Contents | Start | Previous | Next |